Why We Don’t Fear Inflation

/One of my favorite Aesop fables is about a miser who hides his gold coins in a hole in his garden. Every day he digs them up, looks at them, and then buries them again. But he never spends the gold coins.

One day he digs open his hole to find that his gold coins had been stolen, and his heart is broken. And as he cries over that empty hole, a stranger asks him why he didn’t spend any of the coins. When miser responds that he could never spend it, the stranger throws a rock in the hole and says it’s worth the same. If the miser was never going to spend the money, then why did he care if he had pile of gold or a pile of rocks?

The moral of the story is that possessions are only worth what you do with them. If you do nothing, then they are worth nothing.

That’s not quite true in the modern world, since you need some extra money for a safety net, but it’s an effect that can come from deflationary environment. If the value of money keeps going up, no one will spend it. If no one is spending, then no one is buying. If no one is buying, then businesses are dying… The slow version of this is a stagnant economic system. The fast version is a crisis. No one wants deflation.

But everyone on the Internet seems to fear inflation even more.

It’s easy to understand that fear. Over the past 12 months, the price for agricultural raw materials (timber, cotton, wool, and hides) has increased by almost 20%. Food prices are up about 40%. Commodity metals (copper, aluminum, zinc, etc.) are 85% higher. The price of oil has doubled. The prices for all commodities have gone up, on average, by about 50% over the past 12 months. The latest official inflation numbers reported a 5% increase in the Consumer Price Index, the fastest rate of inflation since 2008. Excluding food and energy, the “core” inflation rate was 3.8%, the fastest rate since 1992. The Producer Price Index (considered a predictor of future inflation) rose by 6.6%, the fastest on record.

This is already having an effect on business performance, with companies scrambling to lock in materials prices and raise their own prices. Warren Buffett’s comments at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting included seeing “very substantial inflation” with rising costs and rising prices.

The Federal Reserve does not see this as a big deal. It considers this year’s potential inflation to be a temporary response to the pandemic, and sees persistent inflation as unlikely. Fed officials point to the sharp rise and quick fall of lumber prices as an example of what we should expect in other markets. At the same time, Internet influencers keep telling everyone to buy gold or bitcoin.[1]

Rising prices for specific markets are not strictly within the broad economic understanding of inflation, but they are relevant to the businesses that operate within those industries. Any major shift in supply or demand can have a dramatic effect on business performance. And tracking down the source of these changes can be instructive for investors who want to understand how the connection between markets affects their investments.

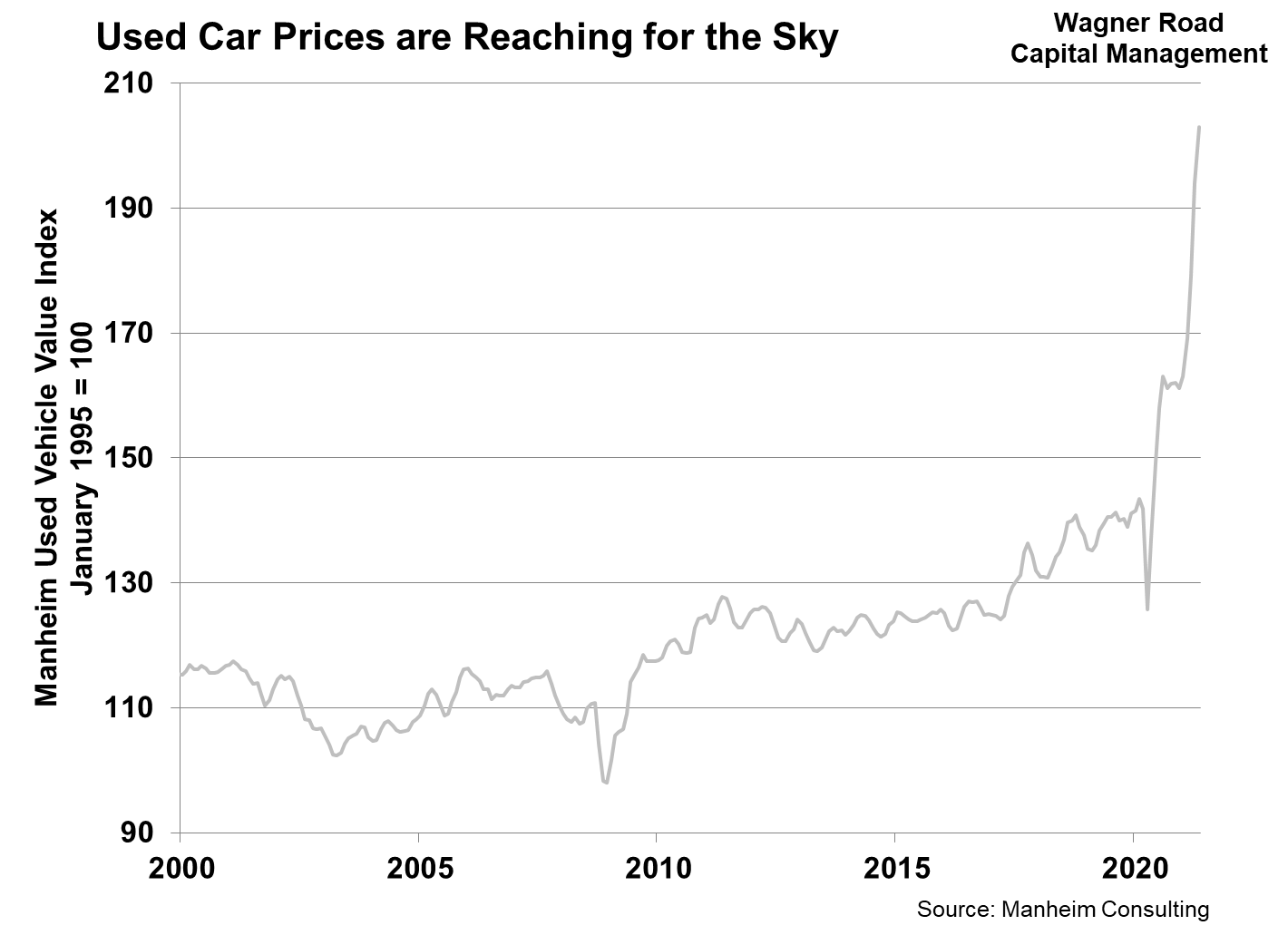

My favorite example of this connection comes from the used car market. Since the start of this year, the price of used cars has exploded.

This is not inflation. It is a single market reflecting the shock of supply and demand changes in other markets. The reason why used car prices have gone up is because there is a shortage of new cars. If someone wants a different car, but can’t find a new one, they will buy a used one.

But this shortage of new cars is not by design. It is by accident. Car manufacturers are unable to get enough microchips to build all of the cars they need. The shortage in cars is caused by a shortage in microchips. The reasons behind this are somewhat complicated, so I’ll use a simplified explanation.

When the pandemic started, the demand for cars fell while the demand for computer equipment took off. To make up for that smaller demand, car manufacturers stopped producing as many cars, while microchip manufacturers adjusted their facilities to focus on the computer equipment market. When the demand for cars returned, the car makers were unable to secure enough microchips, because that production capacity had been filled for other products. Switching back to microchips for cars will not happen quickly, if it happens at all. More capacity is needed, and that will also take time.[2]

The demand side for microchips also complicates producer choices. The start of the video game cycle, the expansion of 5G networks, and the interest in cryptocurrency mining have all contributed to which markets get priority. Right now, cars are near the bottom of the list, and the average wait time for a microchip order is 18 weeks, by far the longest wait time since this metric has been recorded. This is a very good time to be invested in the used car market.

There is still a broader question of rising prices that reach the entire economy, and not just single markets. There is a legitimate concern of persistent inflation and what that might look like. The most common fear goes like this:

The Federal Reserve and the Federal Government pump money into the economy.

This causes severely high inflation.

Business and consumers both suffer.

But that is not quite right. The links between each of these actions is usually based on some incomplete assumptions. I think it’s helpful to start with the last one.

There is wide agreement that consumers are generally hurt by high inflation, but does business really suffer from inflation? (Do rising prices hurt business?) This can be true if inflation is bad enough, but even this effect will be specific to an industry or an individual company. Some manufacturers will get squeezed if their costs go up faster than they can raise prices, but better businesses are able to raise their prices in line with rising costs. Good businesses should be able to raise their prices even faster than rising costs, while the best businesses are in a position to take a cut from transactions and benefit from inflation simply by the default of their existence. Moderate or high inflation is not a serious risk for a high quality company.

But will the Federal Reserve’s actions create a scary amount inflation?

The basic economic theory is that adding money to the economic system will cause prices to rise and create inflation. The reality is more complicated. This connection only works if banks are actually lending the money and people are actually spending it, and it depends on the type of policy tools that the Fed is using. So far, it has not had much of an effect, and we haven’t seen much inflation. Over the past 30 years, we have rarely seen inflation that goes beyond 3%. Over the past 10 years, the Fed has struggled to push inflation above its target rate of 2%. There are a few reasons behind this, but the important thing to note is that the Fed can always reverse what it is doing if inflation goes too far. These policies are not intended to be permanent.

But those low inflation numbers use the Consumer Price Index. The bigger concern among investors is asset inflation, especially the kind that looks like a bubble. Low interest rates force investors to look for higher risk to get the same returns. When bonds become less attractive, people buy more stocks. It also changes the value calculation for different assets. When borrowing becomes attractive, people pay more for real estate. At the highest edges of risk tolerance, you start to see more investment ideas that only exist as a promise to get rich quick—a promise that has no substance. For serious investors, this market behavior can be alarming.

That still doesn’t quite capture the fear of inflation. What these investors are afraid of is not the inflation itself—they own assets, so they are likely to benefit from a rising tide. What they are afraid of is getting caught with too much risk when the tide goes out. The real fear is that asset inflation will end and deflation will destroy investors. The Fed is just a convenient excuse for the fear of making a badly-timed trade. When conditions change, the Fed’s policies will change. Unique circumstances warranted unique actions, and not doing enough was a much more dangerous prospect than doing too much. If the Fed had done nothing, then they’d be blamed for allowing deflation. Investors who take on too much risk should take responsibility for their own trades.

The big unknown for the economy is still how high these price increases will go and how long they will last. Effectively, what we are seeing right now is an increase in demand for goods and services that were held back during the pandemic. This is a one-time event, not a permanent condition, and it should be self-correcting. Over the long-term, either demand will stabilize or supply will increase to meet it, because that’s how markets work.

Andrew Wagner

Chief Investment Officer

Wagner Road Capital Management

[1] From my own training as a serious economist, I find many Internet influencers to be painfully bad at economic analysis. I would not trust their conclusions, and in some cases I wouldn’t even trust their data. While the economists at the Federal Reserve can certainly have some biases, their research methods are worthy of respect.

[2] Production capacity has also been affected by droughts in Taiwan.

Marketing Disclosure: Wagner Road Capital Management is a registered investment adviser. Information presented is for educational purposes only and does not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any specific securities, investments, or investment strategies. Investments involve risk and, unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.